Forging the Future: Decoding India's Green Steel Taxonomy

Introduction: The Furnace and the Future

India has always been a land of builders. From the steel rails that knit its first railways together to the skyscrapers that pierce today's skylines, steel has shaped the country's story of progress. But hidden behind this gleaming alloy is a far less romantic truth: the industry that builds India is also one of its biggest polluters.

At the heart of the challenge is a paradox. India's steel demand is set to explode—from about 150 million tonnes a year today to nearly 500 million tonnes by 2050 , and possibly 790 million tonnes by 2070. This growth is inevitable. It fuels new highways, metro systems, cars, bridges, homes, and factories. But with growth comes carbon. At present, the steel sector emits around 350 million tonnes of CO₂ annually , making up 12% of India's total emissions. And each tonne of Indian steel carries a heavier carbon tag than the global average— 2.6 tonnes of CO₂ per tonne of crude steel versus 1.9 globally.

Left unchecked, the furnaces that forge India's future could lock the nation into an unsustainable carbon trajectory. A business-as-usual pathway suggests over 50 gigatonnes of CO₂ from steel alone by 2070 , far exceeding India's fair share of the Paris climate budget.

It is against this backdrop that the Ministry of Steel has introduced a new framework known as the Green Steel Taxonomy. More than just a policy tool, it is a national re-imagination of how steel should be made, measured, and marketed in an age where climate commitments are as important as economic growth.

The Growth–Emission Paradox

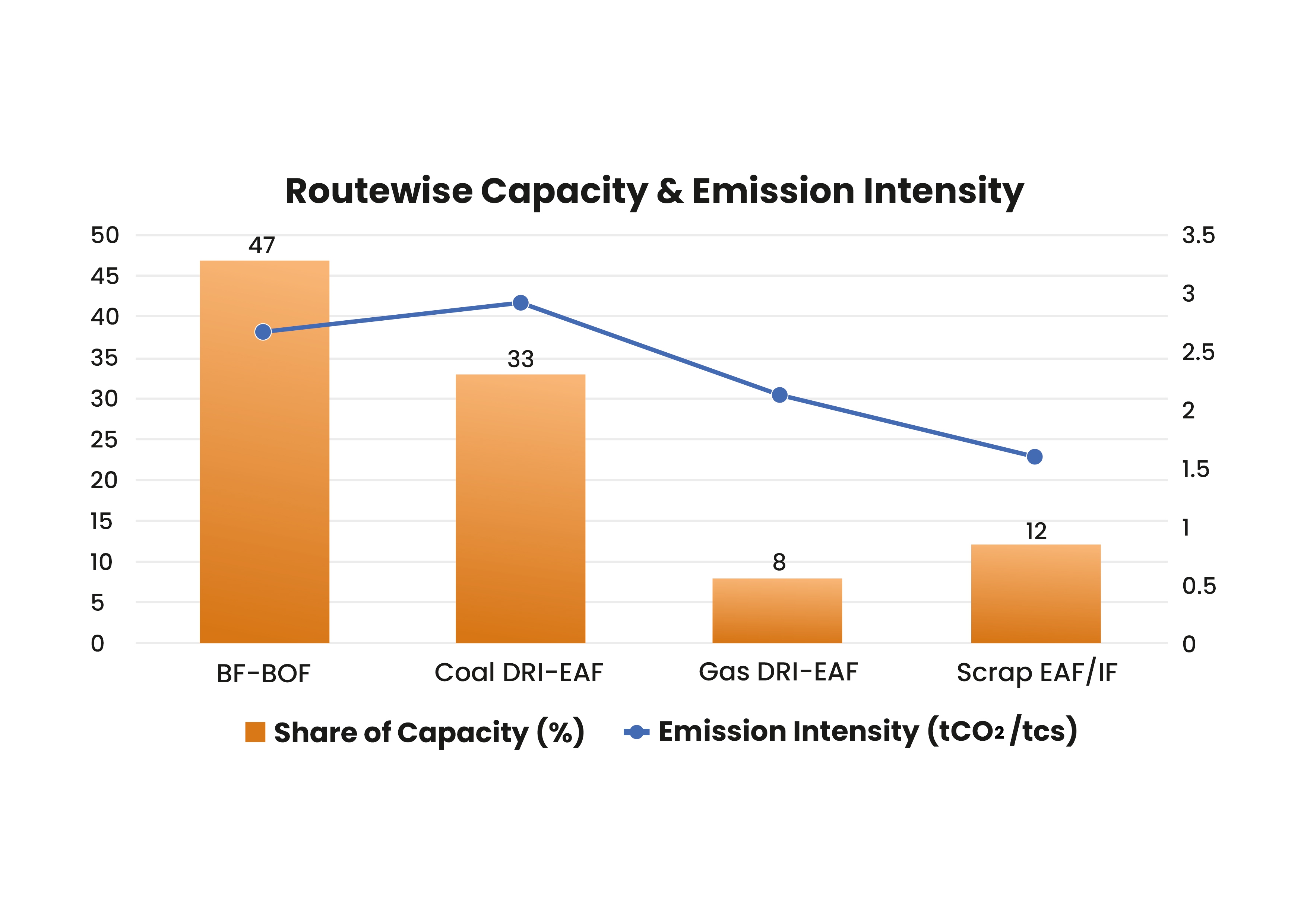

Steel is a "hard-to-abate" sector. Its carbon intensity comes not just from the energy used but also from the chemistry of turning ore into metal. Historically, India's steel journey has been dominated by blast furnace–basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF) and coal-based direct reduced iron–electric arc furnace (DRI-EAF) routes—both heavily dependent on coal.

BF-BOF: ~46–48% of capacity,2.68 tCO₂/tcs emission intensity.

Coal-based DRI-EAF: ~32–34% of capacity,2.91 tCO₂/tcs—the dirtiest route.

Gas-based DRI-EAF: ~7–9% share,2.13 tCO₂/tcs.

Scrap-based EAF/Induction Furnace: ~10–13%, with the cleanest profile at 1.6 tCO₂/tcs.

Source: ISA study on decarbonization

This mix explains why India's steel emissions intensity is among the world's highest. To meet its climate commitments, India cannot continue with this fossil-heavy portfolio. But shifting technology is no small task—it requires raw material readiness, infrastructure, and vast capital investment.

Iron and Scrap: The Material Reality

The road to green steel is not paved with policy alone; it is mined and recycled.

Iron Ore: India's superior hematite reserves (1.5–2 billion tonnes of high-Fe content) will last only 15 years at current extraction rates. Beyond that, India must depend on lower-grade ores or its vast but commercially untested magnetite deposits (~11 billion tonnes). Beneficiation of lower-grade ores could raise costs by $15–20 per tonne.

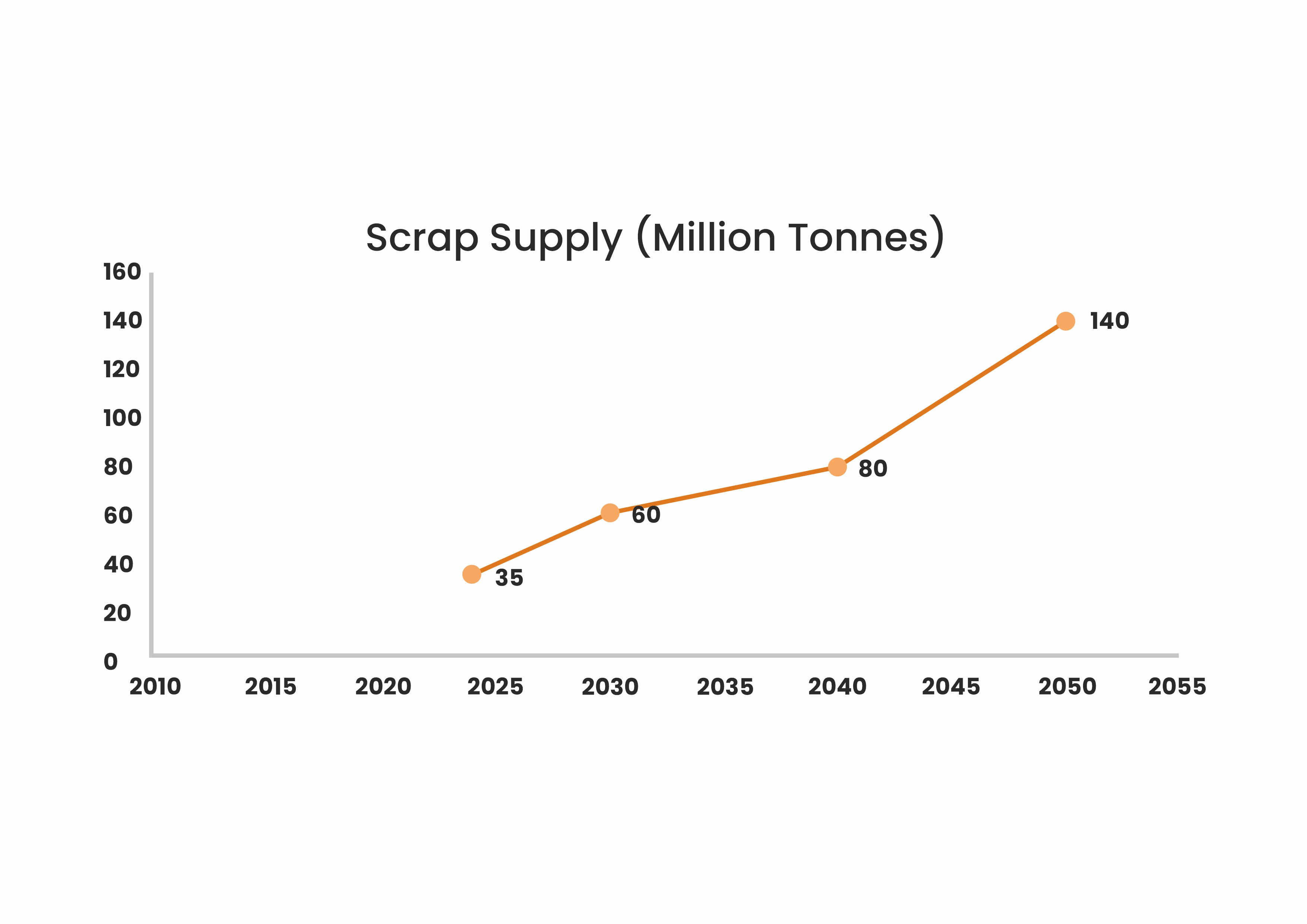

Scrap: Current supply is 30–35 million tonnes per year, while demand is 35–40 million tonnes, forcing imports. By 2050, however, scrap availability is projected to jump to 130–140 million tonnes annually, powered by end-of-life vehicles, consumer goods, and infrastructure recycling.

Source: ISA and AT Kearney Report on Decarbonization

This scrap revolution could be India's ace. Scrap-based EAF production has less than half the emissions intensity of BF-BOF and offers the cheapest decarbonization pathway. But it demands an ecosystem of dismantling centers, shredders, and recycling hubs that does not yet exist at scale.

The Seven Levers of Decarbonization

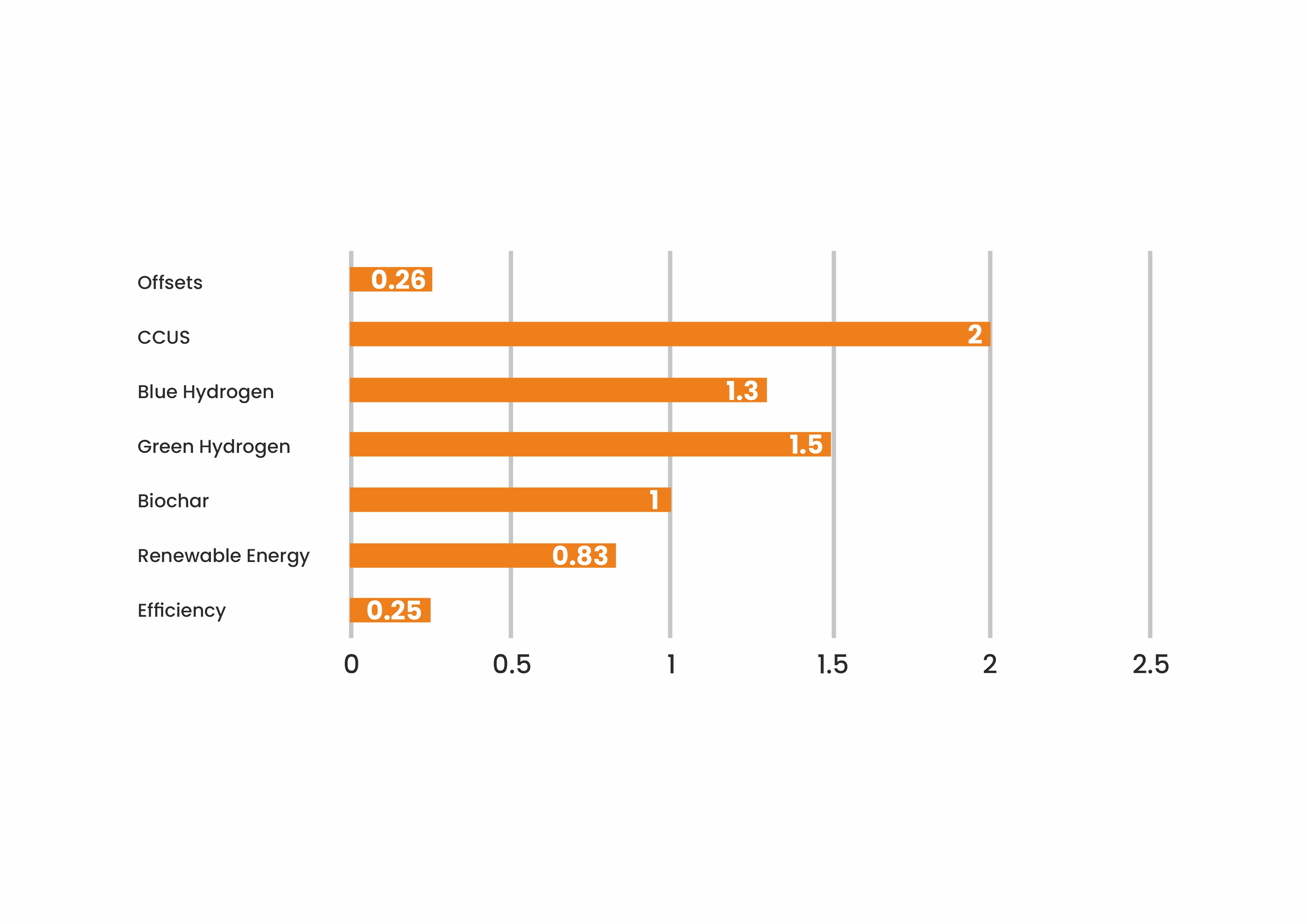

A recent national roadmap outlines seven "levers" that steelmakers can deploy:

1. Efficiency: Measures like coke dry quenching, waste heat recovery, and oxy-fuel burners can

trim 3–10% emissions depending on the route.

2. Renewable Energy: Substituting coal-based captive power with solar-wind hybrids can cut 15–85%

of scope 2 emissions.

3. Biochar: Replacing small portions of coke in blast furnaces with biochar could shave 0.7–1.3

tCO₂/tcs, though supply constraints loom large.

4. Green Hydrogen: At today's $4–6/kg, still costly, but expected to fall below $2/kg by 2040,

unlocking its potential for hydrogen-DRI.

5. Blue Hydrogen: Produced with CCS, potentially cheaper but dependent on gas availability and

storage networks.

6. Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS/CCUS): Essential for abating the last 20–30% of emissions,

though India must still explore storage geology.

7. Offsets: Capped at 10% under global guidelines—useful, but not a substitute for real

reductions.

Source: AT Kearney report

Three Pathways: Walk, Run, Fly

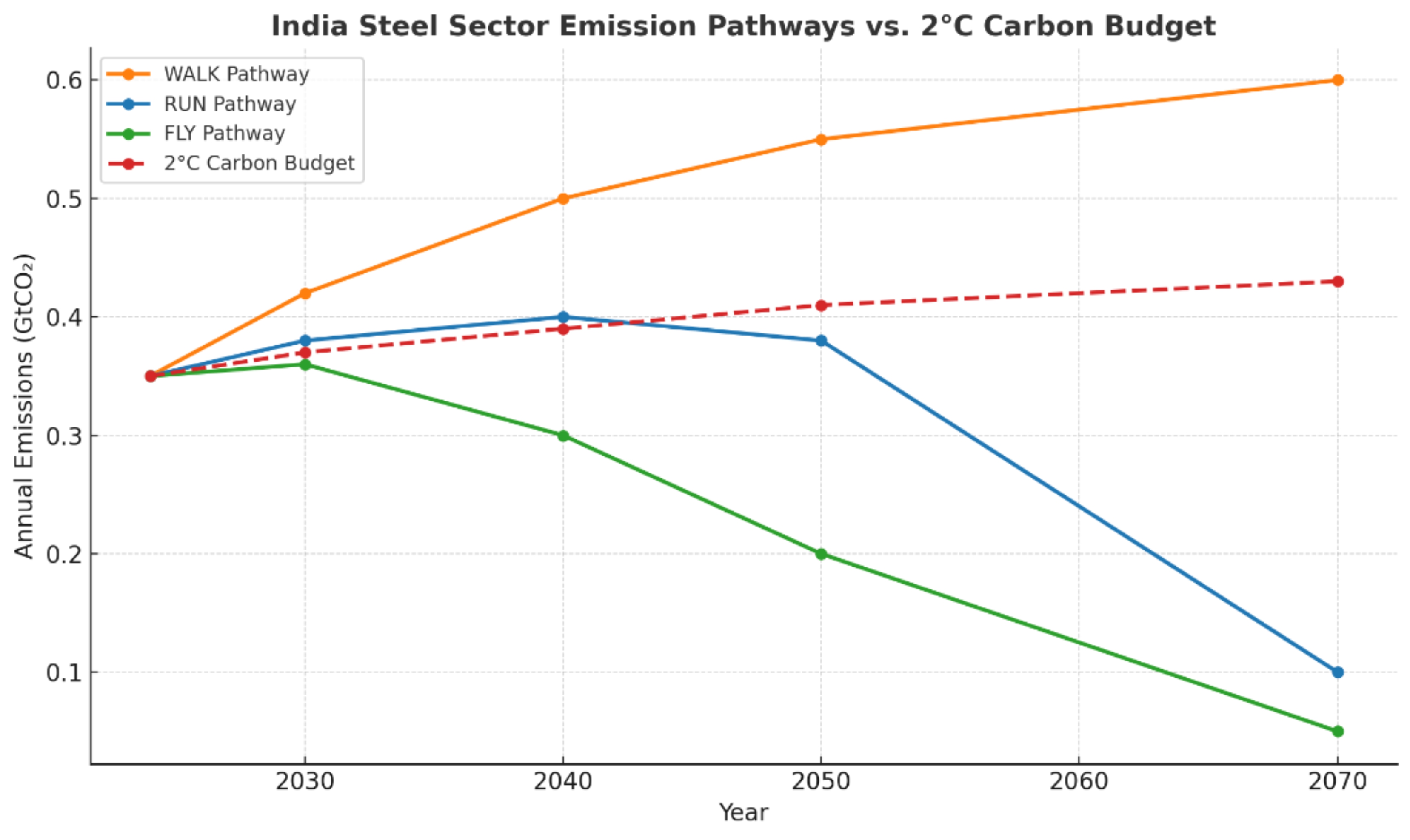

The Ministry of Steel has modeled three scenarios for India:

WALK: A conservative path, focusing only on efficiency and renewable. Affordable, but overshoots

India's carbon budget.

RUN: The middle ground—phased adoption of efficiency, renewables, scrap, hydrogen, and CCS,

ensuring India stays within its fair climate share.

FLY: Aggressive, aiming at rapid hydrogen adoption and deep cuts. Technically possible but

requires unprecedented investment.

The consensus is that RUN is India's pragmatic route: ambitious enough to cut emissions, realistic enough to finance and implement.

The Cost Question

Decarbonization will not be cheap. Estimates suggest:

• Total investment required: $1.2–1.3 trillion through 2070.

• Capex: $420–470 billion.

• Annual incremental opex: $17–19 billion.

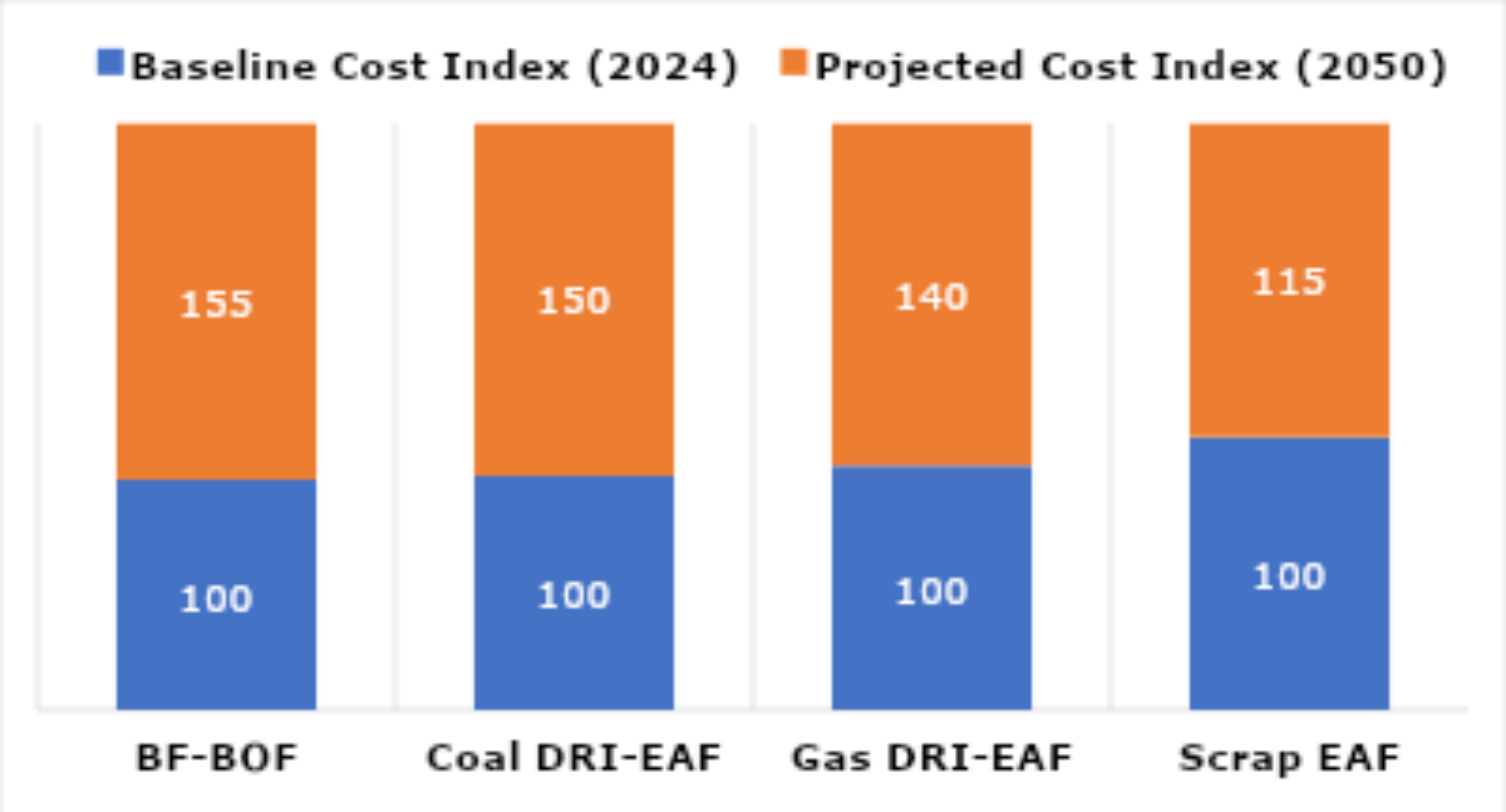

This will push up the levelized cost of steel (LCOS):

• BF-BOF: +50–55% by 2050.

• Coal DRI-EAF: +45–55%.

• Gas DRI-EAF: +20–50%.

• Scrap EAF: +15–20%.

Unless there is a market willing to pay a green steel premium—through procurement policies or carbon credits—producers will hesitate to invest.

Who Will Buy Green Steel?

Globally, demand for low-emission steel is still tiny—about 4–8 million tonnes today—but projected to grow to 40–60 million tonnes by 2030. The EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and corporate pledges from auto giants are creating pull.

In India, private demand is modest:

Automotive (esp. EVs): ~0.2 Mt by 2030.

Consumer appliances (premium segment): ~0.1 Mt.

Capital goods (wind turbines, machinery): ~0.1 Mt.

Luxury construction projects: <0.05 Mt.

Total private sector demand: <0.5 Mt by 2030.

By contrast, public procurement is the real lever. The government buys about 25% of India's steel—over 50 Mt annually by 2030. If even 5–10% is mandated as "green steel," it could generate 3–5 Mt demand annually, enough to jumpstart the market.

The Ministry of Steel's Taxonomy: A Report Card for Steel

For years, "green steel" has been a slippery term. Some companies have claimed it by using more scrap, others by buying renewable electricity, while global labels often set their own benchmarks. The result? Confusion and inconsistency.

To bring order, the Ministry of Steel has introduced a Green Steel Taxonomy—a national framework that sets a clear, measurable yardstick for what qualifies as low-emission steel in India. In essence, it works like a report card for steelmakers.

At its heart is a simple principle: if a steel plant emits less than a certain threshold of carbon per tonne of steel, its output qualifies as "low-emission." If it emits more, it doesn't. The current cut-off is set at 2.2 tonnes of CO₂ per tonne of steel, a line that many of India's existing blast furnace and coal-based plants struggle to stay below.

But the taxonomy goes further. It introduces a star rating system to make the results easy to understand:

• ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ Five-Star Steel: less than 1.6 tCO₂ per tonne (global best-in-class).

• ⭐⭐⭐⭐ Four-Star Steel: between 1.6 and 2.0 tCO₂ per tonne.

• ⭐⭐⭐ Three-Star Steel: between 2.0 and 2.2 tCO₂ per tonne.

• ❌ Anything above 2.2: not eligible to be called green.

To ensure credibility, every claim will be backed by Measurement, Reporting, and Verification (MRV) under India's Carbon Credit Trading Scheme. Producers that qualify will receive Low Emission Steel Certificates (LESCs)—official proof that their output meets the benchmark. These certificates can also be traded, linking green steel to emerging carbon markets and giving companies a financial incentive to decarbonize.

The framework is also designed to evolve. Initially, it will cover direct emissions (scope 1) and electricity-related emissions (scope 2). Over time, it will expand to include supply chain emissions (scope 3) , aligning Indian producers with global standards like Europe's CBAM.

More than a definition, this taxonomy is a tool. It guides investment toward cleaner technologies, helps the government prioritize low-emission steel in public projects, and gives producers a way to prove their credentials in both domestic and international markets. In short, it turns the idea of green steel from marketing spin into measurable reality.

The Policy Roadmap to 2070: Turning Ambition into Action

A taxonomy alone cannot green an industry. Standards provide the direction, but it is policy that builds the road. Recognizing this, the Ministry of Steel has mapped out a detailed policy roadmap stretching all the way to 2070. It is not a single reform, but a bundle of moves designed to support technology, finance, and demand—each one essential if India is to decarbonize its steel sector while continuing to grow.

Here are the eleven pillars of that roadmap, explained simply:

1. Affordable Finance for Smaller Producers

India's steel industry is not just giant integrated plants; it is also thousands of smaller

units that make sponge iron, billets, and re-rolled products. Many of these players lack the

capital to invest in efficiency upgrades or renewable energy. The Ministry proposes

low-interest loans and transition funds to help these producers modernize. Without

such

support, the decarbonization journey will leave them behind.

2. Stronger Incentives for Renewable Energy

Electricity is one of the biggest contributors to steel's carbon footprint. Today, much of

it comes from coal-fired captive power plants. The roadmap extends incentives for

renewable

energy adoption , such as waiving inter-state transmission fees, promoting hybrid

solar–wind

farms, and easing rules for energy banking. The goal: make green power not just cleaner, but

cheaper.

3. Building Natural Gas Infrastructure in the East

India's eastern belt—Odisha, Jharkhand, and Chhattisgarh—is the heart of its steel

production. Yet it lacks adequate natural gas pipelines. To scale up gas-based DRI

plants,

which are cleaner than coal-based ones, the Ministry calls for new pipeline networks capable

of moving 10–12 million tonnes of gas annually by mid-century. This is as much an energy

project as it is a climate one.

4. Investing in Indigenous R&D

Many of the most promising technologies—like hydrogen-based reduction and carbon capture—are

still imported or in pilot stages. The roadmap stresses homegrown research and

development,

urging universities, national labs, and the private sector to collaborate. By indigenizing

technology, costs can be brought down and access widened for smaller firms.

5. Creating a Biochar Ecosystem

Replacing a portion of coke in blast furnaces with biochar can cut emissions significantly.

But India currently lacks the supply chains to collect, process, and deliver biochar at

scale. The Ministry envisions an ecosystem of biomass collection and pyrolysis units,

supported initially by government policy, before mandating its use (2–5% blending) in

traditional furnaces.

6. Subsidizing Green Hydrogen in the Early Years

Green hydrogen is the future of steelmaking, but today it is too expensive. To close this

gap, the Ministry plans subsidies of ₹130–150 per kilogram in the initial years,

gradually

tapering to ₹80–100 as costs fall by 2040. At the same time, it proposes creating

hydrogen

hubs near steel clusters, with dedicated pipelines to ensure smaller producers have

access.

7. Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) Clusters

Not all emissions can be eliminated through fuel substitution or efficiency. For the

stubborn remainder, CCUS will be vital. The Ministry's roadmap includes the development

of

CCUS clusters —geographic hubs with shared infrastructure for capturing,

transporting, and

either utilizing or storing CO₂. Geological surveys to identify storage sites, such as

saline aquifers or basalt formations, are part of this vision.

8. Scaling Scrap Recycling

By 2050, India's steel scrap availability is expected to quadruple. To harness it, the

government proposes an ambitious expansion: 2,400 dismantling centers and 1,100 shredders

nationwide. This will not only reduce dependence on iron ore but also lower emissions, since

scrap-based furnaces are the cleanest production route available.

9. Expanding the Carbon Market

The recently launched Carbon Credit Trading Scheme is at the heart of India's climate

policy. The roadmap calls for expanding its coverage to all steel producers, ensuring strict

compliance, and allowing trading of Low Emission Steel Certificates (LESCs). By

putting a

price on carbon, the market will make polluting steel more expensive and green steel more

competitive.

10. Public Procurement as a Demand Engine

Government projects—from highways to metro systems—consume a quarter of India's steel. By

mandating that 3–5 million tonnes of this demand be met with green steel by 2030, the

state

will act as an anchor buyer. Paying a small premium (₹2,500–3,000 crore annually) could

kickstart an entire market, proving to private buyers that green steel is viable.

11. Skills and Support for Smaller Players

Technology shifts are not just about machines; they are about people. The roadmap emphasizes

training and transition support for small and medium producers, many of whom struggle

with

awareness, technical expertise, and access to finance. Upskilling programs, technical

hand-holding, and easier compliance will help them stay competitive in a decarbonized

future.

Why This Roadmap Matters

Taken together, these eleven steps form more than just a to-do list. They are a

comprehensive strategy to transform one of India's most polluting industries into a

foundation for sustainable growth. By combining financial support, infrastructure,

innovation, and demand creation, the Ministry of Steel is attempting nothing less than an

industrial revolution—one that keeps pace with India's economic ambitions while aligning

with its climate commitments.

In other words, the roadmap ensures that as India forges ahead, its steel will not just build cities and industries—it will build a cleaner, fairer future.

Conclusion: Forging a New Legacy

Steel in India has never been just an alloy. It has been the very backbone of progress—the rails that carried commerce, the girders that held up cities, the frames of cars and bridges that defined modern life. But in the twenty-first century, steel must carry a different weight: the weight of responsibility.

The Green Steel Taxonomy, introduced by the Ministry of Steel, is more than a bureaucratic classification exercise. It is a statement of intent. It signals to the world that India does not see climate action and industrial growth as rivals, but as partners. It is a bet that the country can build, urbanize, and prosper without breaking the fragile climate balance on which all future growth depends.

Of course, the journey will not be easy. Decarbonizing steel will require trillions of rupees in investment, a re-engineering of supply chains that have run on coal for decades, and a change in how both producers and consumers think about cost and value. Green steel may carry a higher price tag at first, but the true cost of doing nothing— unchecked emissions that could derail India's climate commitments entirely—is far greater.

In many ways, the furnaces that once powered India's industrial age will also shape its climate legacy. The choice before the nation is stark but clear: forge responsibly, or risk being forged by the flames of crisis.

With a clear taxonomy, a pragmatic roadmap, and bold leadership, India has the opportunity not only to produce millions of tonnes of steel, but also to lead in what truly matters: tonnes of avoided carbon. If the vision succeeds, India's steel will not only build bridges and skyscrapers—it will build a bridge to a safer, cleaner, and more resilient future.